One of the brilliant aspects of the Brown Institute’s design is our quarterly “all hands” meetings. Every few months, the Magic Grantees, fellows and staff from the Stanford and Columbia sides of the institute come together to share the progress they’ve made on their projects. The venue alternates — California, New York, California, New York…

With ten grants funded this year, there was a lot to catch up on! The real strength of our all hands meetings is that, while each project seems so different, there are deep connections holding them together — connections that reflect the contemporary complexities of how information is created and shared. In addition to a morning of presentations, we always include plenty of time for people to mix, to share ideas, to explore the creative and research communities in either the Bay Area or New York City. This year, it was a field trip to the Exploratorium’s Tinker Studio.

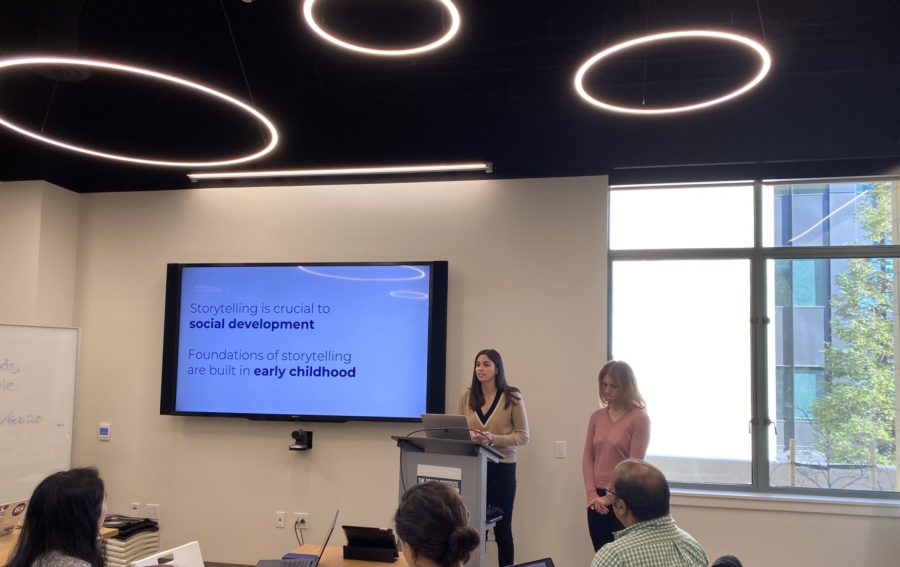

With the entire institute in one room, each team of grantees spent ten minutes reviewing their progress since last Fall’s first All Hands meeting, our kickoff for the 2019-2020 cohort of Magic Grants. A number of projects have finished their initial research and user studies, and have moved on to the early phases of developing prototypes applications. A good example of this is the project A Voice Based Interface for Storytelling and Programming in Early Elementary Years, from Griffin Dietz and Elizabeth Murnane, PhD student and Postdoctoral Researcher in Stanford’s Computer Science Department. They aim to ultimately build a voice interface that will teach five to eight year old kids the basics of computer science by having them interactively script stories. They began their research with a “Wizard of Oz” prototype, where kids interacted with an Alexa “bot” that was actually connected to a human experimenter acting as a scripted agent. In this way they discovered how kids would actually interact with such a device.

They proceeded to demo their early prototype that introduces programming concepts like variables, events, sequencing, and conditionals. It takes the key creative moments of storytelling: say, choosing which animal a story will center on, and frames these as computational decisions, as variables that need to be filled. Writing a ‘plot’ becomes defining a sequential process, a branching narrative: a conditional. When kids describe a storytelling parameter (“kitten!”), their ability to switch this variable out and make the whole thing about a dog (the program will proceed to woof at appropriate moments in the story) illustrates the power of computational thinking. “Cool,” the bot responds to their choices.

The team behind Tech Tweets, Katy Gero, Lydia Chilton and Tim Requarth, has also made significant progress on their Seed Grant. They hosted a writing workshop where they taught scientists, mainly Columbia PhD students, how to communicate scientific research to a wider audience; ‘tweetorials’ are science writing for social media. The workshop highlighted the pain points of writing these longform Twitter threads, namely crafting a compelling intro and determining overall structure for the threads. With these insights, they’ve begun building a creative interface that will help write tweetorials by suggesting things like recent news articles that are relevant.

Cameron Hickey and Laura Edelson, for the project Contrast Agent, have spent their last few months cataloguing the various “Manipulation Service Providers” (MSPs) that sell inauthentic engagement around posts across social media platforms — from YouTube “likes” to followers on Twitter to praise on LinkedIn. One tangible finding of their investigation so far is that engagement is, for the most part, pretty cheap — but you get what you pay for. At the other extreme, they found one MSP selling Instagram “likes” for as much as $2.72 each. That’s the most expensive of any purchased engagement they found (the next most expensive service provider is only about $1). The reasons for this high variance in cost can be partly explained by the different types of inauthentic engagement — getting humans to like, comment, and subscribe is more expensive than tasking a couple clicks from a bot army. The Contrast Agent team is in the process of building a system to automatically capture information about each provider of inauthentic activity, in order to better understand how to spot these bad actors in the wild.

We’ll be profiling the progress of many of the other grants in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!