By Bernat Ivancsics and Bhaskar Ghosh

Yesterday, The New York Times’ R&D team, in collaboration with IBM Garage, released the initial findings of The News Provenance Project (NPP), which began in July. The project is an attempt to curb the growing threat of misinformation by making the sources and origin (i.e. provenance) of journalistic content clearer to news audiences. Bhaskar Ghosh and Bernat Ivancsics, Brown Institute Fellows who worked on the project over the summer, give their insights.

(Bhaskar Ghosh is a second-year dual degree student in Journalism and Computer Science at Columbia University. He has worked as a software developer in the past and is now focusing on computational stories and building tools for the newsroom.)

(Bernat Ivancsics is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Communications program at the Columbia Journalism School. His research centers on data-driven tools used in newsrooms.)

Introduction: Decentralized misinformation, decentralized authentication

Fighting misinformation has become a household chore for news organizations. Misinformation– however you may want to define it–signifies a broad range of phenomena that includes deceptive political campaigns on social media, false information masked as legitimate news stories, or the general slipping-away of legacy news organizations’ gatekeeping role.

Today, stories and articles that appear to be legitime can come from anywhere–news, whether fake or real, has become decentralized. Decentralization is the term du jour. Decentralization also permeates tech, media, finance, and just about any industry remotely capable of extracting abstract value from its assets (money, information, licensing, and so on).

As a result, misinformation is decentralized, too. Propaganda used to come from identifiable sources, such as states’ communications departments or corporations’ press offices. Today misinformation has more subtle forms and sources: opinion sites disguised as news services, comment bots, social media pages. And so it may seem that the solution to decentralized misinformation might come in the form of decentralized authentication or verification. If misinformation scales through networks, authentication must scale through networks too.

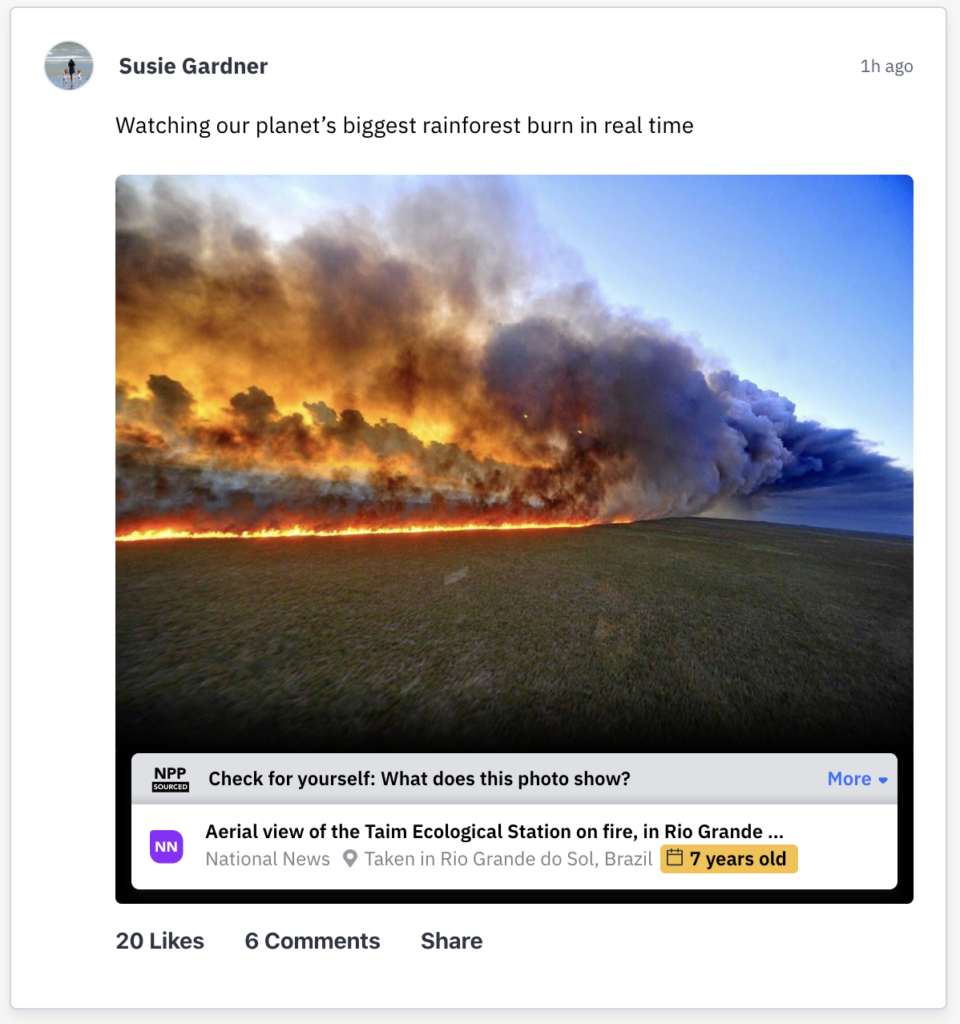

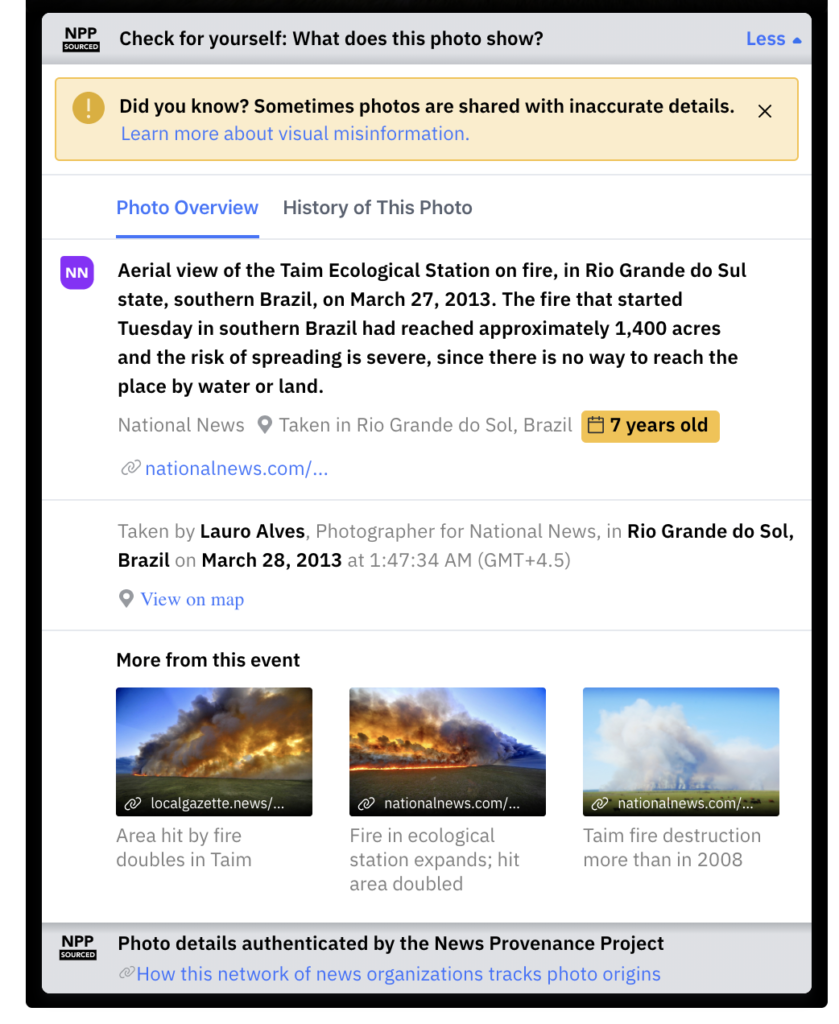

A mockup of the NPP icon that would appear according to the project’s Proof of Concept. Not only does it tell the reader when the photo was taken and which organization verified it, but expanding the icon provides a detailed history of the image’s circulation on the internet.

A mockup of the NPP icon that would appear according to the project’s Proof of Concept. Not only does it tell the reader when the photo was taken and which organization verified it, but expanding the icon provides a detailed history of the image’s circulation on the internet.

The News Provenance Project – Authenticating photos in journalism

The thinking behind the project goes like this: if readers and viewers can peek behind the curtains of journalistic production, they would be more trustful of what they read and hear. The core idea behind the project was that in order to enhance audience trust, we would need platforms and platform applications that would help readers and social media users navigate the tangled landscape of articles, photos, and other forms of media, and allow them to see where those media come from and how they come about. In short, the project has aimed to make the “supply chain” of journalism transparent and navigable for end users.

To achieve this role, decentralized authentication would be supported by a private blockchain network that could store and validate contextual information of news stories. The R&D team worked with IBM over the summer to develop a minimum viable product (MVP) that demonstrates how provenance information on photos could be shown on a social media feed: clickably, unintrusively, but conspicuously. Engineers at IBM used Hyperledger Fabric on the backend to load (via an API) photographic metadata from two publishers and created a social media website to showcase the capability of the blockchain solution.

Yes, photo metadata. In this demo-phase of the NPP we focused on photojournalism and the provenance of images. Why? Images are regularly used in misleading contexts on different social media. Photos can go viral and visual memes derived from photos can become part of our digital-visual vocabulary — this vocabulary often being a lexicon of hate speech or extremist ideologies. Photos and digital images also make for a special case of misinformation: they invite a much more visceral reaction from readers and users than text. The digital images of today can be endlessly copied, modified, stylized, and repurposed in manifold ways. Meanwhile, photos are an important ingredient in the news business as photojournalists take pictures and news organizations publish their photos to illustrate the news, to serve as evidence for the news, and to convey information that newstype simply can’t.

News organizations act on the professional assumption that photos that serve a journalistic purpose (i.e. editorial photography) have an important role to play in the news ecosystem: they must be factually correct, truthful to the situation in which they were taken, and undoctored as they are viewed, shared, or commented on. Editorial photos, thus, have a unique status rooted in their core function to convey factual information and illustrate events truthfully.

But there are political gains to be made when “neutral” and professional-looking editorial photos get reframed in allusive contexts. Editorial photos can be stripped of their context, re-captioned, photoshopped, or meme-ified. Often the motivation is political, other times it’s clickbait. Regardless of the motive, important photos of important events can end up in misleading contexts, such as when crowds of people in a refugee camp are shown to be waiting outside the southern border of the United States, when in fact those same refugees are in Greece and are of Pakistani origin. Or that climate activists leave behind trash during a protest when in fact the photo of the piles of trash is from a landfill in India. The list goes on.

Blockchains and trust

To circle back to the Provenance Project, the NPP team quickly realized that the core technology underlying the News Provenance Project was not a blockchain network, but trust. We made the assumption that if only readers knew how, when, where, by whom, and in what context a photo was taken, they would be much better equipped to judge for themselves that the image they see is showing what the caption and the story around it say it shows. In turn, the transparency of the journalistic supply chain would invite readers and users to engage more with journalistic content and simultaneously trust it more and engage with it more. Blockchains are great for network-based verification, and their chain-like structure provides the necessary redundancy that prevents data from being overwritten or erased.

But we have learned that a bare-bones blockchain network — or even the awareness of its presence — is not enough to build trust in users. In the team’s user research we actually found that users would be confused or become distrustful if they learned that the metadata shown to them with each editorial photo had been “authenticated” by a “blockchain network.” Readers are often distrustful of large, faceless institutions and networks, and they can be especially distrustful of technologies that invoke “gambling” and “dark money” as immediate connotations.

So we dropped the reference to blockchains. We still had to develop a kind of widget or window-overlay that would show up with each photo (on a website or in a social media feed), and invite users to explore the metadata of that photo. We had to find a visual format to display metadata intuitively and to label the widget with a trustable icon that would be recognized across platforms (think of the HTTPS “lock” icon in the URL bar of your browser window). Finally, we had to decide what data points to include in the overlay. Metadata can be a lot of things, not all being equally valuable and informative.

The News Provenance Network – A brief structural overview

Even cursory research shows that the industry standard for tagging and classifying photos is done through the International Press Telecommunications Council (IPTC) standard. IPTC as a consortium defined the fields and values necessary for different media types, and tech companies built out the infrastructure to host these fields in file headers. There are thousands of possible metadata fields and values. Only a few dozen are always used, such as fields related to the photographer and the copyright owner, the caption, the location (country, city, region), and the time zone.

We prioritized including in the blockchain network the fields that could realistically fit into a pop-up window for photos in social media feeds. We decided to keep those fields that relate to the time and place where the photo was taken, as well as many of the fields dedicated to the description of the photo: original caption, caption writer, keywords, people and locations shown by the photo.

One field, however, was missing. Subjects of our UX research have reported that the clue they found as one of the most useful in the NPP test widget was the timeline that showed how the same photo appeared in different publications at different points in time. Backing this, the IBM team created a “Publishing Record” data field, which only the publisher could modify, and which updates organically when a photo gets republished by different news organizations. The original record on the blockchain that contains a photo’s metadata is thus kept unique but remains editable (keeping a record of all edits), and it links to the Publishing Record JSON files which can only be edited by the original publishers. Multiple Publishing Records can link to the original metadata record, and so the journey of the same unique photo can be traced across multiple publications and over time.

Researching credibility

Our work also included mapping the academic and entrepreneurial landscape of various initiatives that attempted to push back against “fake news” and misinformation in general. We reached out to research centers and R&D projects that trod similar paths as us: media forensics projects that developed watermarking algorithms to secure image authenticity; blockchain initiatives that offered some variation of metadata logging and supply chain transparency; smartphone apps that provided blockchain-verified digital fingerprints for photos taken with their photo app; and research groups that looked at how images become viral, how users evaluate the credibility of a source, and how users cognitively conceptualize their own expertise of differentiating between authentic and fake information.

All this research is currently being fed into a whitepaper-style “playbook:” a user guide to an imagined world where decentralized misinformation meets decentralized authentication with news organizations teaming up to regain their foothold as sources of credible information.

The in-house prototype

While the IBM team was building the Hyperledger network, the R&D team decided to also develop a parallel prototype by developing a browser extension to introduce trust signals into the Twitter feed. This browser extension is meant for the hypothetical scenario in which social media companies don’t buy into the private blockchain network idea and don’t use the network’s metadata repository to authenticate published photos in their feeds. We envisioned users still wanting to verify images published on Facebook or Twitter, and so an alternative way had to be figured out to identify photos and compare them to a database of verified metadata. Also, since this extension was built around the time when UX research was actively underway, it aimed to facilitate further research into the formulation of an end-to-end solution from an UI/UX perspective. We chose to develop the extension for Google Chrome, as it is the most widely used web browser.

The expanded overview of an image from the News Provenance Project’s Proof of Concept.

The expanded overview of an image from the News Provenance Project’s Proof of Concept.

The extension works by retrieving the URL of the image embedded in a given tweet and matching it with similar photos from a database of images, alongside their metadata.

Each record in the database is associated with an image and includes photo source, date and location of capture, original caption, perceptual hash and tags associated with the photo.

One of the biggest challenges in this project was to identify ways to map photos found on social media with the photos on the database. Photos on Twitter, for instance, are completely stripped of any metadata or unique ID. All we have is the custom URL generated by Twitter for each photo. To compare a photo on Twitter with images on the database, we decided to use a perceptual hashing algorithm that generates a 64-digit hash value for an image. While it is not a completely fool-proof method to generate a unique ID that would transcend different platforms, it was deemed to be good enough for prototyping purposes.

We retrieved embedded links of images that appeared on Twitter as a user scrolled through his feed and generated perceptual hashes for all of them. These hashes were then compared with the hash values of images in the database to determine if there is a match. Finding an exact match can be difficult because values of perceptual hash changes with the resolution of the image. Photos on the Twitter feed are usually of a lower resolution and size when compared to original images, hence we tweaked the matching algorithm to be tolerant towards difference in the hash value to a certain extent.

We made additional changes in the code to make API requests to the backend as and when tweets became available rather than having the user click on a button on each tweet to fetch information on a given photo. This led to a better user experience in the sense that not only does the user not have to perform an additional click, but since the information is already available, it would be harder to ignore.

Finally, we decided to use computer vision algorithms to add an extra layer of comparison on top of perceptual hashes. We observed that if the photo was modified even slightly, the perceptual hash of the image would change significantly. That would lead the algorithm to conclude that there were no similar images in the database, which is wrong.

We used a computer vision API that would return tags associated with each image, along with confidence levels for each tag. For example, for an image of an empty classroom, the tags could be ‘desk’, ‘chair’, ‘whiteboard’ and ‘computer’ with confidence levels of 90 percent, 80 percent, 60 percent and 40 percent. However, the tagging API returned different tags for the same image under different resolutions. As mentioned earlier, images on Twitter are of lower resolution. This made image comparison difficult, because the tags could mismatch even if the two images were the same.

Hence, in the final stretch, we decided to keep the perceptual hash as the primary metric for comparison. If the hashing match fails, the algorithm returns an empty response. The hashing algorithm can be refined further for better results.

The Chrome extension provided a good platform for the UX research team to analyze different possibilities around the prototype. Since the extension works on Twitter, it is a good approximation of how an end-to-end solution would look and work on a social networking platform.

Notes on the Brown Institute Fellowship

Working on NPP was an important learning experience from the perspective of thinking and conceptualizing a newsroom product. We learned that applying technological solutions–such as a private blockchain network–to social problems–such as trust or the lack thereof– requires deep understanding of the problem and the social context in which it takes place. We had to familiarize ourselves with all potential stakeholders participating in the solution (photographers, editors, technologists, as well as the end users), evaluate how audiences would react to the trust signal being developed, and play out possible scenarios in which such a technological intervention could scale to become a possibly frictionless addendum to online news consumption habits.

Finally, possible future phases of the News Provenance Project will have to test how participating news organizations can govern themselves in such a data-sharing network, and how they can retain the trust of their audiences as they make their news production pipeline transparent for the public.

Further Reading

For more, check out Sasha Koren’s post detailing the project and Emily Saltz’ write-up in the NYT Open blog detailing how users interpret the trustworthiness of photos on social media. Also check out the project page https://www.newsprovenanceproject.com/